Watches with skulls – a symbol of death or a sign of immortality?

The history of the skull symbolism

A human skull is a widely spread symbol in the world's culture. Is a sign of man's mortality. At the same time it is contemplated as the home for soul, human life, and it has been endued with unusual ritual value since ancient times. The Celts considered skull to be a container of spiritual force, protecting the person from evil forces and bringing him wealth and well-being. A skull is also an attribute of Hindu anchorites, a sign of their disavowal from the vicious world on the way to salvation. Apart from that, it acts as an attribute of the menacing Gods of the Tibetan pantheon. Moreover, the Taoist immortals, Xian, are often pictured with enormously big heads to signify the fact that they had accumulated large amounts of the Yan energy throughout their lives. culture. Is a sign of man's mortality. At the same time it is contemplated as the home for soul, human life, and it has been endued with unusual ritual value since ancient times. The Celts considered skull to be a container of spiritual force, protecting the person from evil forces and bringing him wealth and well-being. A skull is also an attribute of Hindu anchorites, a sign of their disavowal from the vicious world on the way to salvation. Apart from that, it acts as an attribute of the menacing Gods of the Tibetan pantheon. Moreover, the Taoist immortals, Xian, are often pictured with enormously big heads to signify the fact that they had accumulated large amounts of the Yan energy throughout their lives.

In Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” Yorick's skull is presented as a symbol of man's life caducity, his powerlessness against death's face. It seems that it was not so long ago when friends were admiring Yorick's quick wit and sense of humour, but now his bones are lying in the grave. “Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft. Where be your gibes now? Your gambols? your songs? your flashes of merriment, that were wont to set the table on a roar? Not one now, to mock your own grinning? quite chap-fallen? Now get you to my lady's chamber, and tell her, let her paint an inch thick, to this favour she must come; make her laugh at that”. This extract can also act as a reminder about the fact that we will all die, sooner or later, drawing a parallel with the Latin phrase “Memento Mori”. In ancient Rome that phrase was said during the triumphal marches of the Roman military commanders, returning home with victories. The slaves, standing behind their backs, had to remind them that regardless their victorious battles, they remained mortal.

The Muslims connect the famous saying with the fact that a man's future is written down on his forehead with the curves of the skull bone's seams, reminding letters. The Muslims connect the famous saying with the fact that a man's future is written down on his forehead with the curves of the skull bone's seams, reminding letters.

A skull together with a scythe and an old lady is included in the base set of death symbols. It is also an attribute of pictures of many Christian saints and disciples, such as Paul the Apostle, the saint Magdalene, the saint Francis of Assisi. Anchorites are also often drawn with skulls, symbolizing their frequent thoughts about death. Some Christian icons with the scene of Crucifixion are drawn with skull and crossbones under the foot of the mountain and are a reminder of Christ's death on the cross. According to a legend, this cross stands on Adam's bones and thanks to the Saviour's crucifixion on them, all people were meant to gain eternal life.

Different fortune-tellers used human skulls for various magic ceremonies, for example, they put it at a bed's head and called it to tell the future. In alchemy the term “dead head” was used to call the decay products, left in the cup and useless for further actions or transformations. In a metaphorical sense it is something senseless, a dead head, a kind of rubbish. The ancient people of Sabines thought that a human soul is contained in his head, that's why they produced their ritual cups of human skulls. The preeminent medieval Jewish philosopher and one of the most prolific and followed Torah scholars and physicians of the Middle Ages, Rabbi Mosheh Ben Maimon, was making incensing of myrtle around a human skull, Rabbi Eleazar described a way of producing a teraphim (a tribal household god) – slaughter the first-born, cut his head, marinade it and place a gold plate with inscriptions under its tongue and wait for news from it. The first teraphims appear in the Bible in connection with Saint Rachel. She takes them away from the house of her father, Laban from Mesopotamia, which leads us to a conclusion that the cult of teraphims came to the Israeli from the Arameans. Rachel stole Laban's teraphims for the skull not to inform her father about Jacob's escape. The anachronisms of the Lemurian teraphims cult can be seen in Christianity – Adam's head, and in the Reich's occultism, where there was a whole special order and a division, called “Totenkopf” or “The Dead Head”. Even in contemporary life a red teraphim's head has been one of the symbols of the Moscow film festival for a certain period. news from it. The first teraphims appear in the Bible in connection with Saint Rachel. She takes them away from the house of her father, Laban from Mesopotamia, which leads us to a conclusion that the cult of teraphims came to the Israeli from the Arameans. Rachel stole Laban's teraphims for the skull not to inform her father about Jacob's escape. The anachronisms of the Lemurian teraphims cult can be seen in Christianity – Adam's head, and in the Reich's occultism, where there was a whole special order and a division, called “Totenkopf” or “The Dead Head”. Even in contemporary life a red teraphim's head has been one of the symbols of the Moscow film festival for a certain period.

The “Adam's Head” or the “Dead Head” (Germ. – “Totenkopf”) is the symbol of death and, at the same time, of fearlessness in its face, pictured as a skull with 2 crossed bones under it (mostly in white or silver colour against the black background). The skull and bones, as the most decay-resistant and the least subject to decomposition organic matters, have symbolized the ability for physical revival, life energy and spirit endurance instead of being the messengers of horrification, destruction and death in many world's cultures for multiple ages. The “Adam's Head” symbol is close to the pirates' “Jolly Roger”.

A skull has been a symbol of death and the caducity of life, natural for all living beings since ancient times. A human skull alone or being a part of complicated compositions is one of the most widely spread pictorial plots.

The Christian roots

A skull with cross-bones in traditional Orthodox culture has an established name of “Adam's Head” and has an ancient Christian origin. According to the legend, Adam's remains were kept in the Golgotha, where the crucifixion took place. By the Orthodox belief, Christ's blood washed the sinful impurity off Adam's head and all the humanity in his face by God's will, giving all the people hope for salvation. Thus, Adam's Head has a deep symbolic meaning of spiritual death abolition and salvation in traditional Christian sense. You can see the image of a skull in many Crucifixion or Cross paintings, for example, in a traditional monk's schema.

History of the symbol's usage in warfare

Throughout all the humanity's history the symbol of the “Dead Head” was used by the British, the French, the Finnish, the Bulgarian, the Hungarian, the Austrian, the Italian and the Polish military forces mainly in cavalry, air, flame-throwing, assault and tank forces, US special forces and some other regiments. In the old German states, Prussia and Brunswick, both cavalry and infantry units with skulls and crossbones, used as the emblems on their uniform headgear, existed there. In the beginning of the XVIII century the symbol of death became extremely popular among the Western European countries' military units. At that time the basis for the uniforms of Russian, Czech, German and other countries' shock troops' uniform was created. Throughout all the humanity's history the symbol of the “Dead Head” was used by the British, the French, the Finnish, the Bulgarian, the Hungarian, the Austrian, the Italian and the Polish military forces mainly in cavalry, air, flame-throwing, assault and tank forces, US special forces and some other regiments. In the old German states, Prussia and Brunswick, both cavalry and infantry units with skulls and crossbones, used as the emblems on their uniform headgear, existed there. In the beginning of the XVIII century the symbol of death became extremely popular among the Western European countries' military units. At that time the basis for the uniforms of Russian, Czech, German and other countries' shock troops' uniform was created.

For the first time the Dead Head as a part of military uniform was used in the middle of the XVIII century by the strike hussar regiments of Frederick the Great (“the hussars with the Dead Head” or “Totenkopfhusaren” in German). The Prussian hussars' frightening uniform consisted of the black jodhpurs (tight-leg riding pants), a dolman (a hussar tunic), a hussar's pelisse and a black mirliton hat (“Fluegelmuetze” in German) with a silver skull and crossbones emblem on it, symbolizing the cryptic unity of death and war on the battlefield.

The “death and immortality” mnemonics appeared in about XVIII century in the British army as well, namely – in general Wolfe's 17th Lancer Regiment. The general was killed in the battle for Quebec during the war with the French. In 1854, during the Crimean War, after the disastrous attack of the British Light Brigade, destroyed by the Russian artillery and infantry (called “The Charge of the Light Brigade in the Valley of Death” in the British military history) during the battle for Balaclava, the symbol of the Dead Head got another meaning. The skull and the cross-bones were placed above the crossed lancer spears, leaning on the ribbon with the words “Or Glory”, meaning “Death of Glory” (some time later the spears were taken away from the symbol, but the skull and the ribbon were left). British Light Brigade, destroyed by the Russian artillery and infantry (called “The Charge of the Light Brigade in the Valley of Death” in the British military history) during the battle for Balaclava, the symbol of the Dead Head got another meaning. The skull and the cross-bones were placed above the crossed lancer spears, leaning on the ribbon with the words “Or Glory”, meaning “Death of Glory” (some time later the spears were taken away from the symbol, but the skull and the ribbon were left).

The Dead Head also served as an emblem to Frederick William, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel's “Black Brunswickers”, who fought against the French occupants up to the fateful Waterloo battle in 1815. Their symbol became the prototype for a special “Brunswick type” Dead Head. The Dead Head was also the symbol of the French “Death Hussars” regiment (“Hîussàrds då là mîrt”), consisting of the French royalist immigrants, who fought against the revolutionary order, that settled in the Russian army too.

The symbol's usage by the Russian Emperor's Army

In the Russian Emperor's In the Russian Emperor's.jpg) Army the “death and immortality” mnemonics was first used during the 1812's Patriotic War by one of St. Petersburg's militia regiment with the horrifying name of the “Deadly” or the “Immortal Regiment”. That unit's officers' headgear had silver badges with a skull and cross-bones. In the Russian army that symbol was used more as a sign of immortality, rather than the symbol of death (judging by the regiment's name). Army the “death and immortality” mnemonics was first used during the 1812's Patriotic War by one of St. Petersburg's militia regiment with the horrifying name of the “Deadly” or the “Immortal Regiment”. That unit's officers' headgear had silver badges with a skull and cross-bones. In the Russian army that symbol was used more as a sign of immortality, rather than the symbol of death (judging by the regiment's name).

The skull and cross-bones headgear emblem was officially confirmed by Emperor Nicholas II in the beginning of the XX century as a symbol of one of the regular cavalry regiments of the Russian army – the Alexandrian hussar regiment. The badge of Her Majesty's 1st Squadron's 5th Alexandrian Hussar Regiment was “all black with a silver Adam's head (the regiment emblem), framed in a silver hussar chevron”; the 2nd squadron's badge was “all black with a silver Adam's head”.

The Dead Head also appeared on the hats' crowns of the officers of the 4th Mariupol Regiment and the black flags of the 17th General Baklanov's Don Cossack Regiment. As The Sytin's “Military Encyclopedia” states, general J.P. Baklanov, who became very popular in Russia due to his multiple heroic acts in the Caucasus, once was staying at the Groznaya fortress and “he got a postage, unknown from where and from whom. When it was unpacked, there was a black silk flag in it”. The flag was furnished with an embroided Adam's Head, framed by the motto, repeating the final phrase of the Christian Faith Symbol: I hope for resurrection of the dead and for the new century's life, Amen”. “That exact darksome flag brought panic to the Chechens – the biographer adds, – and Baklanov didn't part with it till the end of his life”.

The Caucasus War hero's tomb at St. Petersburg's Novodevichye Cemetery has a memorial, set up for voluntary donations (the general died penniless and he was buried for the Don army's money). The monument pictures “a rock with a Cossack hat and a cloak on it with a Baklanov's flag, seen from under the hat.”

Use of "dead head" during World War II

The use o "dead head" The use o "dead head" as a symbol of military security detachments is down to the fact that most of the first SS-men was in the Freikorps, fighting for the preservation of the German conservative values against liberalism and Bolshevism. Initially, the symbol of a "dead head" of the Prussian type was taken as a base. The members of Hitler’s “administrative security” also choose "Totenkopf" as a symbol of their division in 1923, using initially a few emblems, left from the time of World War II. When the stock of symbols has been exhausted, the SS leadership made an order to the Munich firm of Deshler to produce a great number of "dead heads" of the original sample. as a symbol of military security detachments is down to the fact that most of the first SS-men was in the Freikorps, fighting for the preservation of the German conservative values against liberalism and Bolshevism. Initially, the symbol of a "dead head" of the Prussian type was taken as a base. The members of Hitler’s “administrative security” also choose "Totenkopf" as a symbol of their division in 1923, using initially a few emblems, left from the time of World War II. When the stock of symbols has been exhausted, the SS leadership made an order to the Munich firm of Deshler to produce a great number of "dead heads" of the original sample.

The "Dead Head" was the only remaining part of the SS uniforms throughout the long history of the organization (of course, not counting the generally accepted party’s swastika). The SS-men chose that symbol for their emblem not because they were intended to "intimidate" or "scare" their political opponents. In contrast, a "dead head" was considered to be a positive sign in Germany at that time. According to the famous British military historian Robin Lumsden, "the German Nazis perceived a" dead head ", first of all, as a historic emblem of some elite units of imperial Germany".

At that it would be wrong to ascribe.jpg) a monopoly on the use of "dead head" to the SS. It should be mentioned that besides security units, the symbol of death was used as an emblem and some parts of the Wehrmacht. a monopoly on the use of "dead head" to the SS. It should be mentioned that besides security units, the symbol of death was used as an emblem and some parts of the Wehrmacht.

By 1934 the Prussian symbol appeared on the Standards of armored units in Germany. And the leadership of the SS created and approved a new sketch of the "dead head" with the lower jaw. The new emblem differed by a large anatomical accuracy. From the same period the emblem was issued in multiple versions: with a skull, turned to the right, left, and in front view (the latter two options were used less often than the first one).

The members of all divisions of the SS with no exceptions wore skulls on their headgears. The symbols of death were associated among the members of the organization with courage and military self-sacrifice, but in ideological terms - with the fight against liberalism and Bolshevism.

Besides headgears, the "dead head" decorated rings, daggers, flags, standards, gorget chains, drums and trumpets of the SS. So the chief of the organization, Heinrich Himmler, wanted to show that the SS-members were proud of their emblem, and thereby, at every opportunity they told its history.

Symbol of skull in horlogerie

Next we’ll speak about watch models, the design of which somehow has the skull symbol.

Peter Heynlen from the German Nuremberg created the first pocket watch in the shape of the bulb with a spiral winding spring in 1504. At that the form of the case could be both geometric (oval) and skull- or cross-stylized. The dial was protected by the cover, in which holes in the form of rosettes with petals were often cut that allowed to see the current position of the hand.

Paradoxically, the skull was an often repeated symbol in the pocket watches for several centuries. In fact, on the second thought, all the watches in the world count the time, left for us on the Earth.

Mechanical watches with smiling skull and animated snakes in eye-sockets

Despite the fact that these Despite the fact that these.jpg) watches are about 400-years-old, the effect produced by their jacquemarts is much more impressive than the effects of any modern film. At first minute it might seem that the skull is smiling, then it seems that it is laughing, and, finally, its jaws clench harshly, and it seems that it is trying to bite something. At that one of the snakes is slowly disappearing in an empty eye-socket, and another one is crawling out of the second eye only to suddenly return to its shelter, while the first snake jumps out again. To find out the time, one should simply open the top cover of the skull. watches are about 400-years-old, the effect produced by their jacquemarts is much more impressive than the effects of any modern film. At first minute it might seem that the skull is smiling, then it seems that it is laughing, and, finally, its jaws clench harshly, and it seems that it is trying to bite something. At that one of the snakes is slowly disappearing in an empty eye-socket, and another one is crawling out of the second eye only to suddenly return to its shelter, while the first snake jumps out again. To find out the time, one should simply open the top cover of the skull.

That watch was designed in 1610 by Nicholas Schmidt der Junger in the German city of Augsburg in the form of a skull, fixed on crossed cannon bones, set on a stand from gilded brass, with hinged cover, which hides the dial. From the bottom the stand is provided with a hexagon support of ebony. The dial is made of silver and decorated with floral patterns, performed by enamel technique “Champlevé”. The watch has only one hand, made of gilded brass. The tilting gearing of these old watches with vertical escapement is equipped with plate from gilded brass with domed props, additional drum with chain, steel balance wheel with two levers, no spring, engraved and perforated cover of balance movement from gilded brass, fixed screw, provided with a fastening for installation of ratchet-wheel. The mechanisms of automatic jaw and snakes in the sockets are controlled by two 6-speed eccentric washers and put into action by an additional drum, rotating at the speed of 20 rotations per hour, so the jaw is fully opened in 3 minutes and then abruptly closed, at the same time one of the snakes sharply emerges from the eye-socket, and another is hidden. The height of the watch with the stand is 14 cm.

Watch of Queen of Scotland Mary Stuart

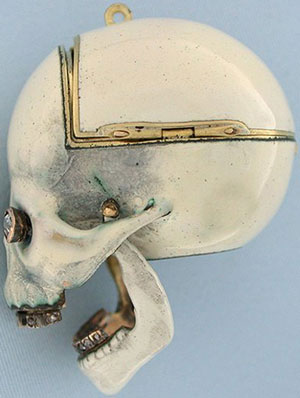

.jpg) Shortly before Mary Stuart Shortly before Mary Stuart.jpg) was beheaded, that scary silver watch in the form of skull was created for her. The case opens at opening the lower jaw, attached to hinges; the movement takes the place of the brain. On the dial there is only the hour hand. This watch is one of the earliest interpretations of the trend "Memento Mori" in watchmaking and artistic sign of human mortality. The original movement with hand engraving was improved by installing a balance spring in the XVIII century. was beheaded, that scary silver watch in the form of skull was created for her. The case opens at opening the lower jaw, attached to hinges; the movement takes the place of the brain. On the dial there is only the hour hand. This watch is one of the earliest interpretations of the trend "Memento Mori" in watchmaking and artistic sign of human mortality. The original movement with hand engraving was improved by installing a balance spring in the XVIII century.

According to legend, Queen of Scotland presented that unique watch to one of her ladies in waiting, Mary Seton. The skull is made of silver of exceptional quality and engraved with lines of the famous Latin poet Horace, figures of Death with a scythe and hour-glass, images of Adam and Eve, as well as scene of the Crucifixion. The lower part of the skull is perforated in the form of symbols of Crucifixion for the sound of the striking could be heard. The movement is set in the skull at the place of the brain and connected with a silver bell, occupying the entire cavity of the skull. The hours are stricken by a little hammer at the bell, moving on a separate chain. The watch was supplied with a leather case, made in the form of skull, applied to cover the watch when it wasn’t used.

That miracle of watchmaking visited many museums in the world, such as the Museum of Taft Art, Walters Art Museum, Museum of Fine Arts in the Institute of Munson-Williams - Proctor, the British Museum. Its location at the present time, unfortunately, is not known.

Watch-skull of 18-karat gold with diamonds

Initially, portable clocks were Initially, portable clocks were.jpg) attributes of wealthy and powerful people, thus, as if showing their power over the time, which they could move from place to place. The skull, as well as the crossbones, remained an unusual form of the watch case for 400 years. The “bun” form of pocket watches was preserved in the course of centuries, becoming slightly "flattened" and more familiar to us. attributes of wealthy and powerful people, thus, as if showing their power over the time, which they could move from place to place. The skull, as well as the crossbones, remained an unusual form of the watch case for 400 years. The “bun” form of pocket watches was preserved in the course of centuries, becoming slightly "flattened" and more familiar to us.

Germany and Switzerland became important centers of watchmaking, while France and Britain also began to produce watches. It seemed that the Swiss watchmakers, such as Isaac Penar and his mentor Jacques Serman, were predisposed to time meters of unusual shape; they are both known for their “skull” watches, manufactured in the early 17th century.

By the early Victorian era the fashion of epatage and antique things had appeared. The masters of the middle and late 19th century made watches in the form of skulls for wealthy collectors, equipping them with the most modern movements of that time. Among the wealthy middle class of the industrial era there were more people with rising incomes, and affluent members of the society also began collecting expensive skull-watches of smaller sizes.

That watch is made of 18-karat gold in the form of skull and dated 1810; the eyes and teeth of the skull are encrusted with diamonds. The folds of enamel skull open, showing the dial, and at the bottom of the skull there is a small glazed aperture, through which one can observe the work of the movement. This model has been recently sold at the Ebay online-auction for $ 18,000.

Pocket watch-skull from Paul Ditisheim

The famous Swiss watchmaker created that unusual watch in about 1930. The lower jaw of the skull opens, and the silver dial with large Roman numerals and the author's name at the top becomes visible. The dial is equipped with central hour and minute hands and a small second counter at "6" hours. The height of the watch is about 3.81 cm, the depth - 3.17 cm, the length - 4.76 cm. The back of the skull is engraved with the Latin phrase "Nosce Te Ipsum" - “Know thyself”. Now it is impossible to buy the watch by the famous watchmaker, since it is in a private collection.

Other models with skulls

.jpg) There are also many There are also many less known time meters in the style of Memento Mori. For example, the watch of the Renaissance with gilded edge and engraved with Kronos, the Greek god, symbolizing the time, on the dial. The watch was sold at the famous auction Sotheby's for $ 5,000 in December, 2010. less known time meters in the style of Memento Mori. For example, the watch of the Renaissance with gilded edge and engraved with Kronos, the Greek god, symbolizing the time, on the dial. The watch was sold at the famous auction Sotheby's for $ 5,000 in December, 2010.

The model from sterling silver, equipped with a chain with crossbones, the covers of which are fixed on hinges and open, allowing to store there the keys for movement winding, is also very interesting. The forehead of the skull is engraved with the Latin reminder of mortality - the phrase "Memento Mori". The dial is made of frosted silver, the Roman numerals are applied by black enamel. The height of the skull is 4.1 cm, the length with the chain - 33 cm. The estimated price for the watch is $ 15,000 - $ 20,000.

The Latin phrase "Tempus Fugit", engraved on the dial of this little model of pocket watch, means "transient time". A small silver human skull opens, presenting the dial, engraved with several motifs of skulls with crossbones. The model is a symbol of fleeting time. According to the records of the watch’s owners, it belonged to Queen Mary of Teck, the wife of King George V. The Queen presented that unique watch to Henry Wellcome in 1930.

In the early 20th century, many watchmakers of the Old World were creating watch copies in the form of skull or with skulls on the dials for collectors. Even now there are a few watchmakers who manufacture high-quality watches-skulls from sterling silver, which are often lost in the sea of Chinese skulls from cheap material, coated with a layer of metal and provided with quartz movements, which have flooded the market.

|